Laryngospasm

Complete or incomplete closure of the vocal cords and laryngeal muscles

Incidence of 4.2 per 1000 in ED sedations

Laryngospasm is one of those rare life-threatening events in EM that a provider needs to be familiar with before encountering. While well known to the anesthesia community due to relatively high perioperative frequency, it is most pertinent to the EM community in the setting of ketamine sedations. Most studies agree that risk factors are younger age and recent URI (OR 2.03-6). It is thought that airway irritability will typically take 6-8 weeks to resolve after a URI.

Identification:

In complete glottic closure, no sounds may be heard and the chest is often silent. In partial closure, there may be stridor, guttural noises or paradoxical chest movement in effort against the partially closed cords. Apnea identified by chest wall movement or quantitative end-tidal CO2 may be the only indication of laryngospasm.

In a review of 189 cases of perioperative laryngospasm, 77% were clinically obvious, 14% presented as airway obstruction, 5% as regurgitation, 4% as desaturation. 61% of laryngospasm was associated with desaturation.

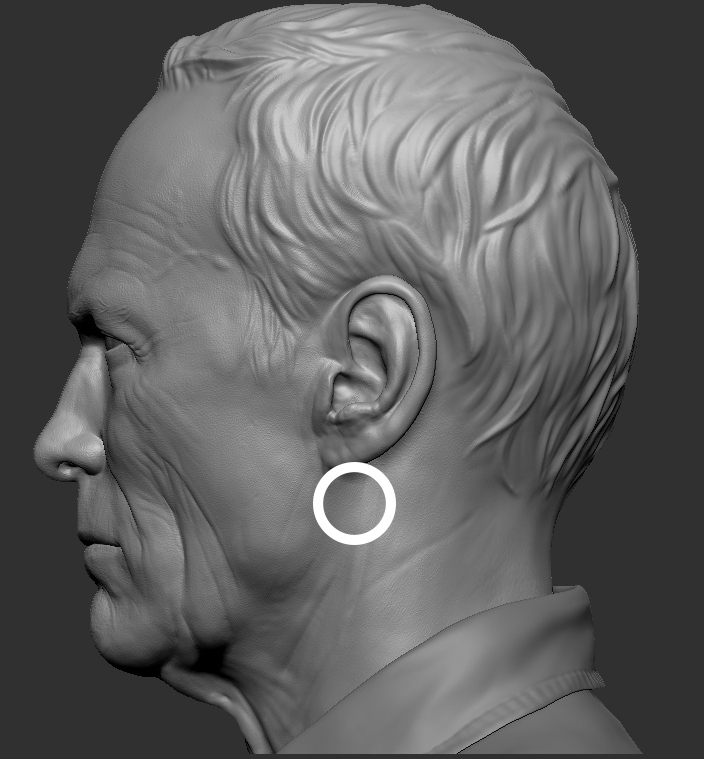

All of these maneuvers should be combined with pressure on the “laryngospasm notch” aka Larson’s point, located between the mastoid and ear lobule and pressing inward with jaw thrust. Periosteal pain results in autonomic nervous system reflex and vocal cord relaxation. One small case series actually visually demonstrated the efficacy of the using this maneuver in two patients undergoing bronchoscopy.

Treatment:

Step one: removal of the offending stimulus; meaning stop the sedation. There is debate that perhaps further deepening of sedation could alleviate laryngospasm. This could mean more ketamine or adding an additional agent such as propofol or versed however there is no data on the topic and only expert opinion.

Step two: management will largely depend on if the laryngospasm is complete or not. First maneuvers should be basic airway maneuvers such as opening the mouth, neck extension and jaw thrust. This should be followed by positive pressure via BVM with a PEEP valve and 100% FiO2 if desaturation continues.

In the perioperative arena, 28% of patients responded to oxygenation via positive pressure.

In a completely closed glottis, it is unlikely that any of these interventions will help. If these maneuvers fail to oxygenate the patient, the next step would be to use medications.

Step three: Medications:

- Propofol (1-2mg/kg) has been shown to treat 80% of laryngospasm.

- Succinylcholine is considered the gold standard for treatment. It can be given at low doses as well as routine: 0.1-0.5mg/kg and 1-3mg/kg, respectively. Low doses may offer the benefit of maintenance of spontaneous breathing. May also be given IM if necessary.

It is rare that a patient is paralyzed in the emergency department without intubation and special attention would be needed if that route was pursued.

Step four: observation for 2-3 hours after laryngospasm for reported post-obstructive pulmonary edema (3-4%), bradycardia (3%) or pulmonary aspiration.

Summary:

- Identify laryngospasm by characteristic noises or apnea

- apply basic airway manuevers such as jaw thrust, opening the mouth and head positioning

- Apply pressure to the laryngospasm notch

- Apply positive pressure with BVM with a PEEP valve and 100% FiO2

- If desaturation continues progress to propofol or succinylcholine

- Intubate if ultimately necessary

Written by Terren Trott

References:

![]() Laryngospasm With Apparent Aspiration During Sedation With Nitrous Oxide Babl, Franz E. et al. Annals of Emergency Medicine , Volume 66 , Issue 5 , 475 – 478

Laryngospasm With Apparent Aspiration During Sedation With Nitrous Oxide Babl, Franz E. et al. Annals of Emergency Medicine , Volume 66 , Issue 5 , 475 – 478

![]() Al-Alami, Achir Ahmad, Maria Markakis Zestos, and Anis Shehata Baraka. “Pediatric laryngospasm: prevention and treatment.” Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 22.3 (2009): 388-95

Al-Alami, Achir Ahmad, Maria Markakis Zestos, and Anis Shehata Baraka. “Pediatric laryngospasm: prevention and treatment.” Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology 22.3 (2009): 388-95

![]() Shinjo T, Inoue S, Egawa J, Kawaguchi M, Furuya H. Two cases in which the effectiveness of ‘laryngospasm notch’ pressure against laryngospasm was confirmed by imaging examinations. Journal Of Anesthesia [serial online]. October 2013;27(5):761-763

Shinjo T, Inoue S, Egawa J, Kawaguchi M, Furuya H. Two cases in which the effectiveness of ‘laryngospasm notch’ pressure against laryngospasm was confirmed by imaging examinations. Journal Of Anesthesia [serial online]. October 2013;27(5):761-763

![]() Bellolio, M. Fernanda et al. “Incidence of Adverse Events in Adults Undergoing Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis.” Ed. Christopher Carpenter. Academic Emergency Medicine 23.2 (2016): 119–134.

Bellolio, M. Fernanda et al. “Incidence of Adverse Events in Adults Undergoing Procedural Sedation in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta‐analysis.” Ed. Christopher Carpenter. Academic Emergency Medicine 23.2 (2016): 119–134.

![]() Visvanathan, T. “Crisis management during anaesthesia: laryngospasm.” Quality and Safety in Health Care 14.3 (2005)

Visvanathan, T. “Crisis management during anaesthesia: laryngospasm.” Quality and Safety in Health Care 14.3 (2005)